Day 2 of 7: The Science of Habits

Only 1 of every 2 persons get to Day 2, so, good on you! High five! :)

Today, we will learn some more about habits and the science of behaviour change. By understanding how our brain works, we are empowered to change ourselves for good.

Habits and the human brain

hab·it: an impulse to do a behaviour with little or no conscious thought, acquired by repetition

Our brains rewire to make repeated behaviours less effortful for us with each repetition, until they become automatic. That's what we call a habit.

The human brain is the result of millions of years of evolution, when sources of energy weren't sitting in the shelf of the corner store. Energy is precious, and our brain optimizes every last bit of it.

Making decisions is an energy intensive task for the brain, and habits are the solution, they are automatic decisions and responses to situations we've faced several times before. Thus, the more you repeat an action, the more the structure of your brain adapts to become efficient at it.

At a lower level, each repetition strengthens the connections between the neurons responsible to deal with such activity. Neuroscientists call this long-term potentiation. The more a neuron to neuron signal is fired the easier it is to relive it, until it becomes the path of least resistance. Automatic. That's how we get good at things, by reinforcing impulses.

What should stick with you is... repetition is the key to forming habits, and since starting small requires less energy, it makes the habit more likely to occur.

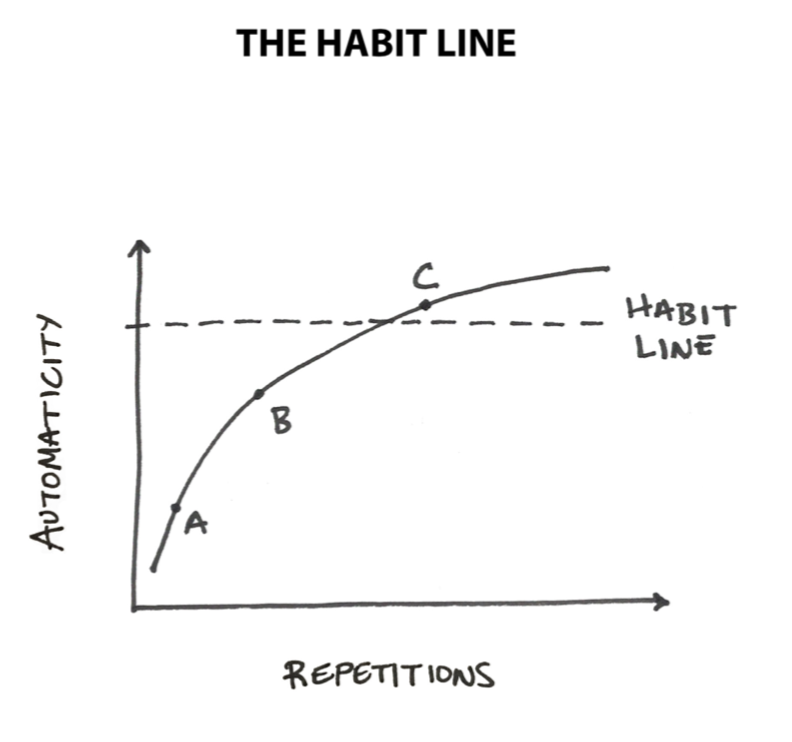

The Habit Line

(from J. Clear's Atomic Habits)

(from J. Clear's Atomic Habits)

The Habit Line defines the point in which enough repetitions lead a behaviour to be more automatic than conscious. A new habit has been formed.

At this point you may be wondering, where's that line?

Well, as you might have guessed, that line highly differs from person to person and behaviour to behaviour. That's why focusing on a certain number-of-days goal is pointless, albeit it does play a role in motivating us to get started and build that early streak.

But I've heard you can form habits in 21 days?!

Again, it depends on the habit and the individual. However, let's face it, 21 days is a number we are all happy to believe in because of how low it is. That's another quirk of our brains, they tend to believe in the things they want to be true. Don't get us wrong, studies prove that in 21 days you can form specific simple habits, but the average for a habit to be automatic seems to be closer to between 2 and 8 months. Still want a number? Ok! The average of those studies was 66! ;D

The point is that the number doesn't really matter, it's a motivational target; you just need to care about the journey.

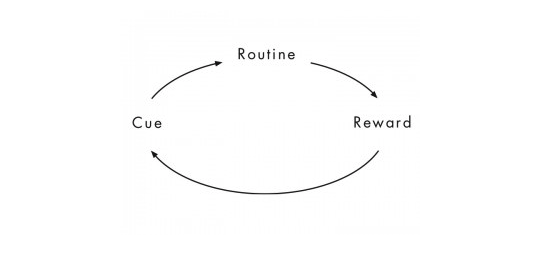

The Habit Loop

(from C. Duhigg's The Power of Habit)

Neuroscientits at MIT discovered the simple dopamine-driven feedback loop that governs habits by observing the activity in rats' cerebral cortex while running in mazes. The habit loop consists of three parts:

Cue: An input that triggers the brain to start a behaviour.

Routine: The actual thought or action.

Reward: The end satisfying goal we crave for.

The cue is noticing the reward and the routine is the action necessary to obtain it. We chase rewards because they are satisfying, they make us feel good. However, it is the anticipation of a reward -not the fulfillment of it- that gets us to take action. The brain uses this mechanism to decide which actions are worth remembering. This is how we learn.

So, how can we hack into this loop?

-

First and foremost, we need to identify the routine. Whether it is the routine we want to perform or the vice we want to get rid off. We can analyze our own existing habits and discover the cues that trigger them or the rewards that keep us performing them. This way we can copy behaviours we are happy with, and try to substitute bad routines.

For example, I wanted to eat healthier, particularly, more fruits. Thus, "eating an apple" is the routine I wanted to perform. My job was to find a reward and a cue that worked for me.

-

The second step is to experiment with rewards. We need to figure out what makes performing such action satisfying to us. Note that we insist in the "to us". What works for one person might not work for the other and that's why we need to experiment.

I knew the long-term reward was better health, but I needed to find a short-term reward that got me to do it every day. I tried telling my sister every time I ate one. (Yep, she still talks to me ;D) I tried to associate eating a fruit after dinner with the reward of watching a talk. Then I started trying to eat apples when leaving home, where the reward was meeting friends or going out for a walk. This sort of catched on, and I later realized which was the actual reward: I slowly came to believe that people smiled more at me just because I was eating healthier!

-

Finally, isolate the cue. The cue is the anticipation of the reward that triggers us to act. Experiments suggest that the majority of cues fall into one of this categories: location, time, emotional state, other people and the immediately preceding action. Thus, context plays an important role.

Soon, it was obvious that the cue to eating an apple was leaving home. I'd take the keys and immediately think of grabbing an apple from the fridge, wash it and leave. I've now been eating fruits pretty much every day for over a year!.These steps are particularly useful when you want to break a bad habit, since once you detect the three steps of the habit loop, you can act on them. For example, being aware of a cue that leads to a bad habit can help you change the routine that comes after it.

Everyday can serve as the cue for a few habits thanks to reminders or by sitting in the new tab of your browser if you use the web version too. At the same time, marking habits as done and seeing your beautiful board acts as a reward that strengthens your routines!

On identity and mindset

Our behaviours shape the way we think, not only about the world but also, and most importantly, about ourselves. They define our identity and beliefs. For example, if you bake your first cake ever and it's good, you'll see yourself as as a good cake baker. Which, guess what? That belief is going to lead you to cook more cakes, actually making you better at baking cakes! On the other hand, you may think you are bad at learning languages, which already undermines yourself at any shy attempts to pronounce déjà vu properly.

Of course some people are innately better at this or that thing, but what this means is that by trusting in ourselves and repetition we can reshape a big deal of our aptitudes and beliefs. We can change our identity into that of the person we want to become. That's the growth mindset.

Thus, mindset defines behaviour, but behaviour defines mindset too. You can't change your mood but you can change the behaviours that affect it! Personally growing is a constant battle between feeling "I'm good at this" and "I suck at this" where you keep showing up, again and again, day after day, every day ;)

You read this far? You are awesome!

Several important concepts were crammed into Day 2, but hopefully you feel much more knowledgeable and empowered now! You can read more on this and other topics on the science of habits in the Learn tab.

You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems.

James Clear

5 days to go!

See you tomorrow! :D